Barend Wind: ‘The Netherlands is one of the leaders when it comes to inequalities in housing.’

Barend Wind: ‘The Netherlands is one of the leaders when it comes to inequalities in housing.’

Since the 1980s the mortgage market in many European countries has been liberalised. In these countries, which include the Netherlands, inequalities of wealth have grown enormously. Below, sociologist Barend Wind talks about the housing policies in other European countries and what the Netherlands can learn from them.

Your doctoral research looked into the relationship between inequalities of wealth in a number of European countries and those countries’ housing policies. To what extent do housing policies and wealth inequalities fit together?

Very strongly. In almost the whole of Europe home ownership has been encouraged, but not always in the same manner. Since the Second World War three groups of countries can be discerned. In the first place there are the southern European countries such as Italy, Spain and Portugal, where houses are in the main the property of the family and where home ownership has been able to grow due to widespread tolerance of illegal building and illegal occupation of public land. In the second place are the German-speaking group, Germany, Switzerland and Austria, where much less has been done to encourage home ownership. There a great deal of effort has been put into the building of private rental accommodation, with extremely stable rents in a regulated rental market. Thirdly comes a large group of countries, which includes the Netherlands and the Scandinavian states, where governments have actively promoted home ownership with mortgage relief and subsidies for land and for building. Since halfway through the 1980s there has been a major turnaround. It’s principally in Great Britain, the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark where the housing market has been liberalised and it’s precisely in those countries where inequality in housing has grown enormously.

Why have house prices in Germany risen so little over the years?

Germany has pursued very conservative policies in relation to spatial planning, the economy and housing construction, and this has turned out a good thing when it comes to the distribution of wealth. Urbanisation is much less pronounced in Germany than it is in the Netherlands. There is still plenty of industry and employment in the smaller towns, which means that these have remained attractive places to live. By definition this ensures more constant house prices, while what also plays a role is the fact that the mortgage market has not been liberalised, probably because all parties can see advantages in maintaining the existing system. Tenants can save up to buy a house in a fiscally favourable manner. And for the banks and landlords, the latter for the most part self-employed individuals who’ve bought a second house, there are few risks, while the houses offer a stable source of revenue. In cities such as Munich and Berlin the rental market is very attractive and prices there are rising. There’s a weighty political debate going on over the question of whether to impose a maximum level for rents. In Munich they have actually frozen housing costs in order to keep rents affordable.

Despite all of this, the level of home ownership in Germany has indeed risen. how do you explain that?

In Germany it’s risen far less than in other countries. More interesting than the slight increase in Germany is the drop in home ownership in Great Britain since the beginning of this century, which shows that the liberalisation policy there has failed to encourage ownership of property. Britain points the way. The social rental sector is limited to the very poorest; neighbourhoods where many people on low incomes have bought a house are becoming impoverished; house prices and associated debt are growing explosively. Young people, even those from the middle class, can no longer afford a house. On the one hand as a result of the flexibilisation of the labour market, on the other because the price of accommodation is so high. We are seeing the same thing happen in Amsterdam.

In Sweden house prices fell much less sharply as a result of the financial crisis than they did in the Netherlands? Why’s that?

Not only the price of accommodation, but the entire economy was touched to a far smaller extent by the crisis. This is probably because Sweden doesn’t have the euro and is less integrated into the international capital market for repackaged mortgages than is the Netherlands. For a long time the Swedish government had a strong dirigiste role in the economy. This was until halfway through the 1990s the country found itself in an extremely serious crisis, at which point the government took the decision to liberalise the mortgage market. Since then not much has been built. Subsidies for building around which the Swedish system revolved fell away. To give an impression of what happened, five years ago the production of residential property was still at hardy a tenth of the level found in the 1990s. Now there was an enormous movement into the three big cities of Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö, forcing housing prices up precipitously. Sweden is a gold mine for researchers, because everything about its inhabitants is recorded. As a result you can find out where somebody lived in the 1990s, what their income was and the value of housing there. What you see is that people from the lower classes and immigrants were forced by poverty to move to the suburbs, while the upper middle class and the upper class were attracted to the centre of cities. As a result people who bought houses in those suburbs have made a very limited profit or even a small loss, while people who bought in better neighbourhoods have gained sometime between 100% and 200%. In the Netherlands we have hardly any such data, but I’m almost certain that if we did we’d see the same picture as in Sweden.

What would have to happen if the inequalities in relation to housing in the Netherlands are to be reduced?

The first important factor is to combat inequalities of income. The more equal the distribution of income, the more equal will be access to the housing market. In time that will bring about a more equal distribution of wealth. A second important factor is spatial environmental policy. As soon as towns such as Gouda, Tilburg, Helmond and Zoetermeer become more attractive to people as places to live, it will take the pressure off the big cities and therefore also reduce the pressure on house prices. That will in time lead to a reduction in the difference between periphery and core, but you’d still have a problem in the cities. That’s why in hard times the government should invest in poor neighbourhoods. In that way you’d give an enormous boost to the value of houses belonging to people who have bought in these areas and contribute to integration of populations.

Another aspect of housing policy which could be changed: there could be more regulation of the mortgage market through, for example, further reductions in mortgage relief. You might also consider subsidising house purchases by low income groups, as was done here in the 1970s and 1980s. That would be a more effective subsidy than is mortgage relief, because only people who really need it would be considered. And we shouldn’t be afraid to impose a tax on the enormous rise in land prices, because that’s the major cause of inequalities of wealth in the Netherlands. As soon as you make a profit from the rise in the price of land which is a result of government investments, it’s the community which should profiting.

What can we learn from other European countries about narrowing inequalities in housing?

From Germany we can learn how they have regulated the rental market and the mortgage market, and that people are still able to buy their house via the fiscally favourable ‘Bauspar’ regulations. From Sweden, how to subsidise houses for people who want to buy, as they did in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Moreover in Sweden a large slice of the population still has access to social housing, which is essential to a well-functioning system. Also from Sweden, how to combat any stigma attached to social housing, and put downward pressure on the private rental market. And from Belgium we can see at the moment that they are building more social housing than we are. The question indeed is where to start. As a left party it seems very attractive to solve everything via rent subsidies, but then you’re opting for the British system, under which people are being compensated for the suffering brought about by the market parties. I think, however, that market regulation and a healthy housing system for the people are much more effective. The issue is then of course that the government takes back the means to direct the system, powers which it has given away.

Any final remarks?

The Netherlands is one of the leaders when it comes to inequalities in housing. Read Piketty and you’ll see that the enormous growth in capital consists in the main of residential property. Let’s do something about that.

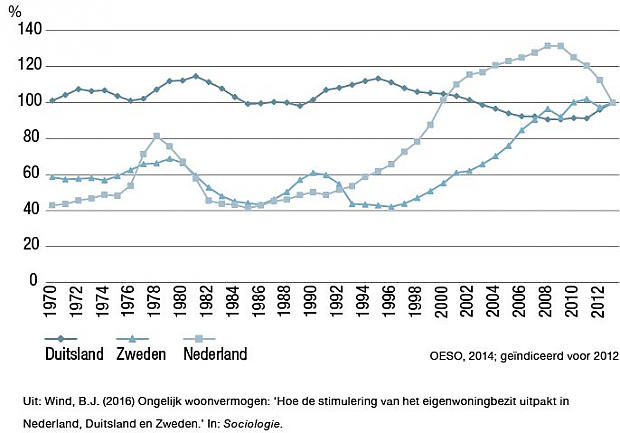

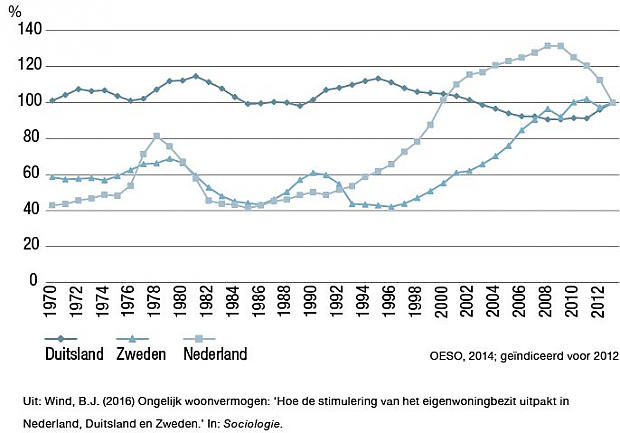

The development of real housing prices

in germany, sweden and the netherlands

This article was first published, in the original Dutch, in the SP magazine "SPanning"