Harry van Bommel and Arnold Merkies: Greeks are setting an example

Harry van Bommel and Arnold Merkies: Greeks are setting an example

The election result in Greece demonstrates unequivocally that voters are seeking alternatives to the heavy-handed austerity policies imposed by Brussels. The European Union’s neoliberal course forces the public to foot the bill for a crisis which they did not bring about, and which merely increases tensions between north and south. Syriza’s victory should give cause for all European politicians to consider a different financial and economic policy in the EU, argue Harry van Bommel and Arnold Merkies.

‘We dare to dream again,’ said the sacked Greek cleaners after Alexis Tsipras’ new government had announced that they would be rehired, and that instead, external ‘political advisors’ would be dropped. A symbolic measure, but one of major political significance. With it, Syriza demonstrated that ‘structural reforms’ – Brussels jargon for harsh austerity – were not forced by economic necessity but were instead a political choice. Where the government of former prime minister Antonis Samaras bowed before the strict budgetary policy imposed year in, year out on Greece by the EU, Tsipras offers another way out of the crisis, one which puts the Greek people’s interests first, rather than those of the moneylenders. This offers prospects for the rest of Europe, too.

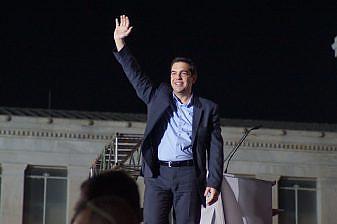

Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras

Tsipras’ plans are twofold. On the one hand Syriza wants, with the EU, to renegotiate Greece’s debt and the macro-economic policy to which Greece is currently bound, and on the other hand restore parts of the welfare state, which under the pressures of austerity has been stripped to the bone. This is urgently needed, as under Samaras the Greeks have seen their economy shrink by 25%, extreme poverty has doubled, while people in financial need eventually saw their access to basic services such as health care and electricity denied. Meanwhile, a quarter of the Greek population is without work, a figure which rises to half amongst young people. Greece will need years to repair the damage caused by austerity policies.

Syriza has made some big promises: the creation of 300,000 jobs, reversal of the cuts in salaries and pensions, the neediest to receive free food, health care and public transport, and ensuring that no longer could people be evicted as a result of being unable to afford to pay their mortgage. Some of its plans, moreover, the government has already put into effect: in addition to rehiring sacked officials, the privatisation of the port of Piraeus and the state energy company PPC will be retracted and the minimum wage raised to €751, the norm before the country was forced to reduce the sum to €500. Syriza wants to see the Greek people in the first place in work, paid a fair wage and provided with a social safety net. Looked at in this way, the economic programme is not radical left, but should rather be called classic social democracy.

In foreign policy too Greece is changing direction. On its very first day the new government made it clear that it did not support the present EU policy towards Russia, that it wanted no new sanctions against Russia because the sanctions policy had not produced the desired effects. In this they are correct. Fresh sanctions will lead to further escalation and that is not only against European interests but plain dangerous. The new government is expected in addition to adopt a critical stance in relation to Israel and to recognise the Palestinian state. The Netherlands should take its lead from this. The Greeks also have stern criticisms of NATO, reproached as a Cold War alliance. These are sore points at European level, and because of that could contribute to a fresh, critical debate on EU foreign policy.

How much of its programme the Greek government can realise is partly dependent on the EU’s attitude, on whether or not Greece can be given the necessary space to invest in its wrung-out economy. This will be negotiated shortly. The EU’s opening position will be to cry blue murder over the bad example that debt relief would set to other countries subject to the European austerity regime. The fact is, however, that pretty well everybody knows that the Greek debt as such is unsustainable. To continue to deny this is to do nothing but throw sand in the eyes of one’s countries own voters, just as was done when the loans were extended to Greece in the first place and people were told, including by the Dutch government, that the money would be returned with interest. For these reasons what’s being sought is a longer payback term for the loans, lower interest rates and forbearance within the Stability and Growth Pact so that the Greek economy is helped and a chance of the debts being paid remains.

The Greek people have voted en masse for a party which is free of corruption and wants to make a serious attempt to address the moral issues surrounding taxation, impose heavier taxes on the superrich and save what’s left of the welfare state. In Spain the electorate might well follow that example. Its fresh policies mean that the Greek government is holding up a mirror to other European countries, one into which, however, other governments don’t yet dare to look. In our view EU economic policy has not led to restoration but to further destruction, and it’s high time it was changed. The Greek election result forms the icebreaker needed to bring about this change, and in that it’s good news for all Europeans.

Harry van Bommel and Arnold Merkies are Members of the Dutch Parliament for the SP and respectively spokesmen on European Affairs and Financial Affairs. A shortened version of their article appeared on 31st January, 2015, in the national newspaper Het Parool.