SP leader Emile Roemer in Brazil: Learning from each other, inspiring each other

SP leader Emile Roemer in Brazil: Learning from each other, inspiring each other

On 9th August SP leader Emile Roemer arrived in Brazil for a working visit in the company of the party’s National Secretary Hans van Heijningen and Brazil specialist Peter Runhaar. Below are extracts from their account of their experiences in Latin America’s biggest nation.

SP: São Paulo

São Paulo

Avenida Paulista, the beating heart of São Paulo, with its to our eyes so familiar SP logo. High rise flats, banks, apartment towers, kiosks, market stalls; antique villas in the green spaces where well-to-do citizens live, if they haven’t sold up to the new property-rich; the modern art museum and views through to lower-lying neighbourhoods. Spaciously laid-out with multi-lane roads on every side, as befits a metropolis of twelve million inhabitants which, adding on the populations of the surrounding commuter towns, gives it a population greater than that of the Netherlands. We are here to visit Brazil’s enormous governing left party, the Workers’ Party (PT) of Lula and Dilma, to exchange experiences with its representatives and to learn from each other.

São Paulo

First we were received at the Dutch consulate by Jan Gijs Schouten who for the lunch has invited a few representatives of the Dutch business community and the three major Dutch banks. These are heavily present in São Paulo due to the extent of mutual trading and investment treaties. Hans Mulder, who has lived in Brazil for twenty-four years and represents the Chamber of Commerce, is optimistic about the country’s immediate future. The protest movement of for the most part students and middle class people, he sees along with further indications as the expression of a living and ever-deepening democracy. He expects a combination of a strongly growing middle class – a result of the government’s successful anti-poverty policy – in combination with greater income equality, to offer countless opportunities for the country’s further economic development.

Visiting the Dutch consulate

Rick Torken of the major Dutch bank ABN-AMRO, informed us about the problems which it had encountered as a result of the credit crisis. In his view the Brazilian government’s guiding role in relation to the financial markets and the extreme professionalism of the Brazilian Central Bank meant that a banking crisis such as that experienced in Europe could not happen there.

Two Brazilian women, a lawyer and a business woman, both of whom spoke extremely good Dutch, told Emile that these days they did not feel as welcome in the Netherlands as once they did. They asked him whether the SP would ever be prepared to govern alongside the hard right, anti-immigration PVV, for example should both parties emerge with massive gains at the next election. Referring to its leader, Emile replied: ‘Not while Geert Wilders’ party continues to want to exclude people on grounds of their beliefs or their origins’, an answer which went down well.

Our next meeting was at the Workers’ Party research department where we met with several people who work at what is the only political party-affiliated institution financed by the state. It is involved in a wide range of activities including not only research, but education, international cooperation, and keeping the party’s one-and-a-half million members informed. In common with the SP the PT does not form part of a single international network, but maintains contact with left, social democratic and green parties abroad. Talking to each other and learning from each other is the approach.

We had an extensive discussion about the protest movement which gathered strength in July in all of the major cities. These protests – against corruption and violence and for affordable, good quality public transport, decent education and accessible health care – were in their opinion justified, but the currently limited power of the PT in Congress makes it hard to respond practically. The system under which business finances politicians while trade unions are forbidden to do so, and thinly populated right-wing regions enjoy a disproportionately strong numerical advantage, makes it impossible for President Dilma to meet the demonstrators’ demands. For this reason she has proposed a ban on private financing of parties and the establishment of a weighted system of parliamentary representation, but these proposals enjoy little support in the current Congress. With the plan unable even to muster the support of as many as a third of the 513 representatives, attempts are being made to collect the two million signatures required under the constitution for an initiative which the Congress will be unable at least to ignore.

Visiting the Workers’ Party (PT) Emile Roemer is on the left, Valter Pomer on the right, with SP adviser on Brazilian affairs Peter Runhaar between them.

At our next meeting, Valter Pomar, a veteran of thirty years in the leadership of the PT, confirmed these views, adding that the elections in October 2014 – in the wake of the World Cup – would be very, very difficult. Winning the presidential election would in itself give insufficient weight unless accompanied by a change in political relations in Congress. Not mincing his words, he summed up the weaknesses in his own party: the following was ageing; and links with the social movements – such as the unions and environmental and student movements – had in some cases become dilapidated. The political culture lacks inspiration and intelligent debate. He confessed to being relieved that the social unrest had gone off the boil. ‘That gives us more than a year to show that we have heard the message and together with the generation that is the first to take to the streets for more than twenty years, get to work on a more social and a better Brazil.’ This last meeting of what had been a fruitful first day ended with Pomar expressing interest in visiting the SP to discuss closer cooperation between the two parties.

The next day we visited a school, before going on to a meeting in the city centre with Ciro Biderman from the town planning and infrastructure department of the São Paulo local authority. He explained to us some of the city’s problem’s, and told us how in his view you had to choose between private transport and public transport, and that for him the choice was obvious. However, Brazil’s car industry is an important interest, and though he had on several occasions proposed that the current limit on free buses be extended to 150 kms from the town centre, he has always been overruled by one of his superiors. However, since July’s mass protests change has been in the air in São Paulo.

'I’ve actually got plenty of practical objections to the demonstrators’ demands,’ Ciro Biderman told us, ‘but I would still consider them my friends. Their protests have shaken the authorities awake and forced them to reflect on matters which a few months ago they would have dismissed as nonsense. When it comes to the water supply the problem isn’t so much quantity as quality. Everywhere you make a hole in the ground, water spouts out of it, but the quality of this water is another matter. The river which goes through the city has been used for decades as an open sewer, causing considerable water pollution. This isn’t a problem that can’t be overcome, but it would take hard to come by investment to solve it.’

The third problem he cites in the council’s management of slums, which are to be found principally in places where in the past the authorities have issued a ban on building. Now, they have no intention of driving the people squatting there out, and don’t want to destroy the social structure which has come into being in the shanty towns. ‘In recent times we’ve offered 50,000 people in these neighbourhoods new prospects’ he says, admitting that this is ‘a drop in the ocean against a background of two million illegally-settled inhabitants’, but, he adds ‘rather long-term solutions than violence that leads nowhere.’ Positive news, he concludes, is that numbers have stabilised, ‘which is a precondition for getting the matter under control.’

Meeting with Lula

Emile Roemer in conversation with the former president of Brazil, Lula.

From this meeting Emile Roemer’s party went on to the Instituto Lula, named for the former Brazilian president, with whom they had arranged to speak. Greeted by a man who turned out to be Lula’s brother, they were then presented to Lula himself, who began by asking them about the left’s influence in Europe, immediately answering his own question, saying that outside of Norway and Denmark it was hard to see any such influence. The ex-president then went on to talk about developments in Latin America. He had been convinced that the left could win elections in the region as long ago as 1988, and two years after that had organised a conference of Latin American left parties. He felt that since then there had been a real revolution, with the left in power everywhere except Columbia, where armed conflict had led to an ascendancy of the right. Many countries would be having elections next year, so we stood on the verge of aan exciting period. They could be proud of what had been achieved: cooperation and trade agreements between Latin American countries and with Caribbean countries, cooperation agreements with Asian and African countries, and for the first time in history they had been able to hold important talks without the presence of the US.

In part under the influence of the crisis which broke out in the US and Europe in 2008, he went on to say, we now find ourselves in a period of rather lower economic growth of – according to expectations – between 2.5% and 3% p.a. This has meant that President Dilma has been forced to carry out necessary economic adjustments, but this has not undermined Lula’s optimism about the future of the country. Unemployment is, at 5.5%, at a historic low; Brazil has discovered its own stocks of oil and gas; and this means that the necessary investments for the improvement of urban infrastructure and the preparations for the World Cup, can be paid for without causing too many problems.

Moving on to talk about the recent protests, the ex-president said that his government had succeeded in reducing the numbers of people in extreme poverty by a total of 46 million people, while the middle class had grown by 40 million. Real wages had risen significantly, while the poor had benefited more from favourable economic development than had the middle class or the rich.

After describing some of the fruits of this growth in terms of flights taken, cars owned and the spread of the Internet – the latter also having implications for the way in which politics has to be conducted – he explained that young people who had attended university in the last few years were demanding not work or better wages, but well-functioning public services, improved education, and more democracy.

Turning to the left in Europe, Lula said that in his view it needed thorough reform. Social democrats were hesitant in their defence of the achievements of the last half-century, while the right was on the attack against foreigners, but were putting on a great show of strength in favour of a healthy environment and on other issues. Neither the Socialist International, nor the G-20 was coming up with any new ideas. The people are uncertain, which presents the left with a challenge in working out new paradigms.

Emile chipped in at this point, adding that ‘the banks have been rescued with enormous quantities of taxpayers’ money, while social programmes are put through the mill. This is at the expense of democracy, because politics is keeping people at a distance instead of drawing them in.’ Lula agreed. With that, and Lula’s proposal for further meetings between the two, the interview came to an end.

Meeting with a World Cup Winner - and other people of São Paulo

Later in the day the SP group visited a project which attempts to combat delinquency in young people by providing, sports facilities, with football under the direction of the former player Rai, veteran of sixty-three internationals in Brazil’s midfield, including those for the country’s victorious 1994 World Cup team. The complex which Rai showed Roemer and his colleagues around has not only sports facilities, but a library, a space for film and theatre productions, computer rooms, music production studios and social work provisions. The place is full of perhaps hundreds of children and young people. They clearly see Rai as a hero and an inspiration.

Rai and Roemer

The centre has been growing for fourteen years from its original base in a disused school building provided by the regional authorities, a building in a neighbourhood ravaged by drugs and criminality. It now serves nine hundred children and has a staff of ninety, as well as local mothers who work as volunteers. Rai expressed most pride in the way that the scheme had succeeded in transforming the whole community. Unfortunately, it relies for about 80% of its funding on corporate donations, yet its achievements are clear. Some of the firms are motivated by the level of their investment in the community; others by fiscal advantages.

Saturday was less intense, with a visit to a park to stroll and chat to local people along with the Dutch consul and his wife, all enjoying the air and the landscape. This was followed by a visit to the Museum of Modern Art, and a long walk through the city centre to the Italian quarter, where a neighbourhood street party was in preparation.

We were making our way to a tree-planting action, a protest against the growing commercial takeover of the Italian quarter, where three new building complexes have recently been constructed. Plans are afoot for an enormous car park, but a sympathetic local authority gives space for action and hope for victory to local people who have alternative plans for a new urban park, rather than a car park. Emile and the others spoke with two young people whom they had met on their visit to the school and who had been involved in the July demonstrations and who wanted to interview the leader of the Netherlands’ left opposition. Raul, the interviewer, turned out to have done his research and was impressively knowledgeable about the SP and a range of live social issues of importance in the Netherlands, such as drugs, prostitution and the cuts in spending on prisons, as well as the general political situation. He positions were then reversed, with the Dutch asking questions of the Brazilians, and the latter admitting that the protests had come as a surprise even to the participants. ‘A lot of people have made progress in the last ten years as far as their purchasing power is concerned, while the level of provision of services has lagged far behind. What’s the use of buses if they spend most of their time in traffic jams? What’s the use of schools if you hardly learn anything in them? Health care and education are expensive, even for the middle class. The increase in bus fares was the spark that set the fire, but what also contributed is that we have for a relatively short time had a left mayor, Hadda from the PT, who has created a new dynamic. Freedom to demonstrate is greater, but at the same time we know that Haddad had the support of big corporations at the election, so he’ll need our help to stick to a good path.’

Police brutality at the first protests and attacks on journalists which put them in hospital contributed enormously to the anger which surrounded the demonstrations, they added. ‘Earlier it was the poor and marginalised people who were on the streets, but now the middle class joined the movement.’ And the political reaction to this movement? Did the PT take the side of the demonstrators out of conviction or opportunism? ‘Opportunism’, says Raul; ‘Conviction,’ says our other interlocutor, Gresley. The fact is that 400,000 people were on the streets, a phenomenon which politics can’t ignore.

Salvador, Bahia - An Afro-Brazilian City

Our next trip a couple of days later was to Salvador, where around 90% of some three million inhabitants are Afro-Brazilians, descended from African slaves. Although the agrarian hinterland of Bahia is overwhelmingly PT, the city itself has for many decades been dominated by a single powerful family, the Magalhaes. The godfather, Antonio Carlos Magalhaes, was pushed to the fore during the military dictatorship which began in 1965, as the strong man of Salvador. He died after a corrupt political career, but the town is now governed by his great-nephew, Antonio Carlos, elected on the basis of his reputation as a crime-fighter. This can’t be divorced from the issue of rising criminality and insecurity in Salvador as the flight from the land has added a million inhabitants to the city, people for whom there is a huge shortage of employment and housing. The PT candidate did much better than his predecessors, but couldn’t win.

Reception centre for homeless old people

In Salvador we visited an old people’s reception centre for those who find themselves alone and on the street in their later years, the Lazarus House, which offers an extraordinary range of help and activities to its guests. From there to the favela Tancredo Neves-Beiru, where we ate, in the company of a locally-based Dutch journalist, as guests of a local family. As always, a lively discussion of politics and other matters ensued, with as many opinions expressed as family members present.

At the end of the afternoon we visited the Bahia offices of the PT, which was full of local 'petistas', including party officials, representatives of the youth movement, and the mayor of a town in the same province, a youthful Fernanda Silva, who explained why she is so proud of her party. ‘In the past the mayor in my town was always a man,’ she said, ‘always old, and always originally from the elite. Without the PT someone from my background could never have become mayor.’ Several people joined the discussion of the emphasis the PT puts on equal representation of men and women before we went on to discuss, once again, the PT’s sympathy and support for the protest movement, mentioning in particular the demands for reform of the political system. There was a great deal of interest also in Emile’s analysis of the state of Europe, in which he put the current crisis in historical perspective and answered questions. The atmosphere was exceptionally relaxed. ‘I have a feeling among these people that I’m at home,’ he said, when we finally said a warm goodbye.

Brasilia

Roemer on the podium alongside PT Chair Rui Falcao

Two days later we were in the federal capital, Brasilia, where we had been invited to attend a major gathering of the PT, the starting point for the election of a new party chair. The meeting was held in the Brazilian Senate complex. When we were welcomed into the hall current chair Rui Falcao had taken the floor. He is standing for reelection, and with him on the platform were five other candidates. After a campaign which will last several months, the party’s membership, which is estimated at between a million and 1.6 million – from a total Brazilian population of 200 million - will vote by secret written and digital ballot.

Former President Lula during his speech

After a number of announcements – including the presence of a delegation from the Dutch SP – Lula gave a speech. He invited Emile on to the podium. In the speech that followed, every time the ex-president mentioned the importance of international solidarity and cooperation with left parties in Europe, our delegation received loud applause. In his address, Lula stressed the need for dialogue with the hundreds of thousands of young people who had taken to the streets, noting that they were resistant to everything which politics stands for, but that the last thing the PT should do is walk away from problems. Recalling that when he first climbed on to a podium to give a political speech, such an act by a worker was not tolerated, and yet the PT had in the last fifty years succeeded in transforming Brazil, reducing poverty massively and enabling children from poor families to go to school and even to university. In short, a new reality had come into being. New challenges and new questions have thus arisen, and the answers to these can come only from a party which is united with the people, and this has been, is and will be the PT’s raison d’etre, Lula assured the meeting.

Parliament building in Brasilia

At ten the next morning we were back at the Brazilian Parliament, where we had meetings with members of the Congress and Senate, with whom we discussed a variety of subjects, including the importance of dialogue between Latin American and European left parties, and specific issues such as drugs policy. Wellington Dias, PT group leader in the Senate, was extremely interested in the eurocrisis, which he feared would have a negative influence on his own country. Brazil was coming under enormous pressure from neoliberalism, he said, and the priority was to protect the incomes of those who don’t earn much to start with. By giving these people chances, you would stimulate economic development. There was a regional problem in Brazil, and after high growth in Sao Paulo and the southern states, other regions must be given the opportunity to progress. Investment in harbours and airports was, he said, a must. Recent oil and gas discoveries offer new prospects for the country’s development.

Roemer with Wellington Dias, PT group leader in the Brazilian Senate

Noting that Brazil had traditionally enjoyed strong relations with North America and Europe, Dias said that while these remain strong, they were working to strengthen economic, political and cultural links with the rest of Latin America and with Africa. Brazil had written off or restructured the debts of many countries and was entering into new trade relations. He was pleased that we would be visiting Venezuela after the death of Chavez. The PT believed that thorough reforms needed to take place there if the left project was to survive into the future.'

At the Dutch Embassy

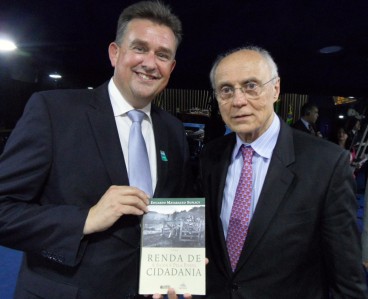

Lunch with the Dutch ambassador followed a brief meeting with a former Senator, the popular veteran Eduardo Suplicy, who despite his wealthy origins has been active on the left for decades, fighting for social justice, education and the incomes of the worst-off. In 2005 he succeeded in having legislation passed on these issues, since when, though Brazil still has an exceptionally poor standing in relation to differences in income, a slow improvement has been effected.

Emile Roemer with former Senator Eduardo Suplicy

Christovam Buarque is known amongst other things as the deviser of the first Bolsa Familia programme, which gives poor Brazilians financial aid providing their children attend school. Buarque sits in the Senate on behalf of the Democratic Workers’ Party (PDT), the Brazilian affiliate of the (social democratic) Socialist International. He welcomed us into his office, a friendly man who can speak with a great deal of authority about education in his country. He was Minister of Education in the first Lula government, but resigned from the coalition cabinet because the government was not in his view going far enough with his idea. ‘Good public basic education, we are achieving that but only after a fashion,’ says Buarque. 'By shifting responsibility from local authority to federal level.’

Later in the afternoon we met with Jose Guimaraes, Chair of the PT group in Congress, where it holds 89 of 512 seats. Guitars switched the focus to political reform, explaining the need to end private financing of political parties, which encouraged corruption. Each candidate conducts his or her own campaign and almost every one is sponsored by a private company.

Together with other left parties, the PT has presented a proposal for a new system of political party financing. This would require a constitutional amendment for which the support of 171 members of Congress is needed, which would enable a referendum in which a simple majority would carry the day. Whether this would be successful, Guimares said, depends on popular pressure. President Dilma has put forward five proposals for reform, but each was rejected by Parliament. ‘But yesterday,’ he added, ‘we presented two million signatures on a petition to force a referendum. We’re not losing heart.’

The rest of the discussion covered the already during our trip to Brazil well-worn ground of Brazil’s coming election and the chances of PT success; the way in this will depend on developments in the economy; and what we had to say about the situation in the Netherlands and Europe. Emile’s last remark before we left was that he was that ‘the way we’ve been received here convinces me that it’s good to make these contacts and that in the coming years we should expand them further.’