Tiny Kox in Russia: Day 4, The times to come

Tiny Kox in Russia: Day 4, The times to come

SP Senator Tiny Kox is in Russia once again to prepare for a Council of Europe observer mission, this time for the presidential elections scheduled for 4th March. He will report daily for the SP website.

Russia is such an enormous country that anyone who can help it to become a functioning democracy with a flourishing economy will deserve a statue.

Grigori Yavlinski from the liberal Yabloko party dreams of such, but it’s unlikely he’ll become president of this immense land, for the time being at least. Not only have the authorities in his view robbed him of a seat in the Duma, they have also refused him permission to stand in the presidential election, the High Court having rejected his claim to have collected the required two million signatures. Has this not left the volunteers who in just a few weeks scoured town and country to gather all of these signatures not sick and dispirited? Not according to what they are saying this morning at the Yabloko headquarters. Yavlinski himself isn’t there, but his old colleagues are. “Our people aren’t despondent,” they insist, “they still believe in our party. But they’re fed up of Putin's attempts to block our access to the political institutions, so this setback will in the end be turned into victory. More and more people are saying – anyone’s better than Putin. That’s partly to our credit. Our time is yet to come.”

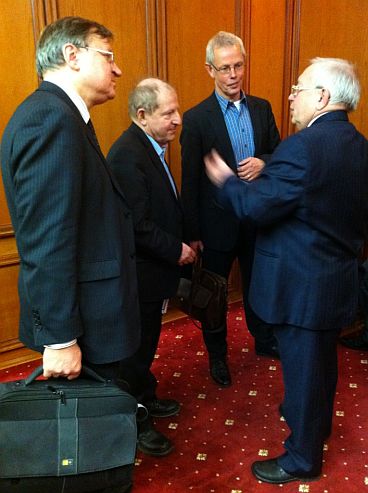

Senator Kox (second from right) at Yabloko headquarters.

“My time has now come”, says Mikhail Prokhorov. The presidential candidate with no party takes his self-confidence into battle against what he calls the ‘Putin collective’, the political veterans who have for years conspired with Putin to prevent Russia becoming a modern democracy with a dynamic economy. He’s not afraid that things will go wrong for him. He knows what happened to Khodorovski, the mega-rich oligarch who meddled in politics and as a result finds himself spending years behind bars. Prokhorov is just as rich. Only two of his compatriots have a bigger fortune than he.

With Mikhail Prokhorov

He earned his money from nickel and cobalt, two of the many raw materials which make Russia potentially the richest country in the world. Now he wants to use his money and influence to become president and create a new Russia, as his election slogan proclaims. He thinks that the times have changed from when Khodorovski was knocked out. Six foot six tall, he welcomes us to his head office and seems sincere. No, he isn’t Putin’s secret agenda, designed simply to draw votes from genuine opponents. He has nothing to thank Putin for, having earned his money before Putin’s rule began. A while back he took the most important decision of his life, to move from business into politics. The first attempt failed, when he took over a moribund party and poured his money into it. This didn’t suit the authorities at all, so they made sure his party was quickly sidelined. Stupid, he calls this now.

“But” he adds, “fortunately I learn just as much from my mistakes as I do from my successes.” And that’s why he’s back. He has, making use of his money, his firms and his managers, gathered his two million signatures, a rigid demand the meeting of which, in reference to Yavlinksi, he describes as “well-nigh impossible and totally humiliating.” Yavlinski should , in Khodorov’s view, have gone straight from the parliamentary elections to the presidential. But it was not to be, and Khodorov is now the only newcomer.

As president he would settle scores with the monopolies which paralyse both the economy and the political system and keep Russia backward. Russia’s place is at Europe’s side. Only together can they successfully resist the two other global power-centres of the Americas and the Far East. He knows that Putin is far in the lead, but if there is a second round, everything will become unpredictable, he says. And if he were to become president? Then he would establish a new liberal party of the centre-right, one for which he sees a big gap in the market, attracting perhaps 30% of the electorate. He has the will, the time and the means, he says, laughing amicably.

With Vladimir Lukin, ombudsman for human rights

In the afternoon I visit the national ombudsman for human rights, Vladimir Lukin. He is a former colleague of Yavlinski, with whom he established Yabloko back in the ‘90s. Now Lukin finds himself in the role of bridge-builder between the authorities and the new opposition who since the parliamentary elections have repeatedly taken to the streets and who dominate the Internet. I have met with him before, in Moscow. Once again he says he sees himself as an intermediary, but that the problem is that the authorities are as yet not reacting. “To clap you need two hands,” he says, philosophically.

Vladimir Lukin (right)