Observing Russia’s elections

Observing Russia’s elections

SP Senator Tiny Kox was head of the Council of Europe observers’ team for the Russian elections which took place on 4th December. Below, he reports on his experiences.

It was already dark when I landed in Sheremetyevo on the afternoon of 30th November. Because it doesn’t put its clocks back, Russia’s time is currently three hours later than ours. The Russian media announced today that all of the international observers had been accredited. This includes me, despite an outstanding objection from the president of the Russian election council, in whose opinion I had, during my initial visit early in November, broken the necessary regulations. My press conference had, it emerged, put his back up. His complaint, however, had not been taken into consideration by the public prosecutor, the foreign ministry or the parliament. I had expected it to be, but the Council of Europe had, the previous week, accepted my proposal that if any member of the observer team were to be denied admission, nobody at all would go. This hadn’t happened, so I knew that the following day I would be able to get down to work. First of all I would go through the necessary documents and see if I knew everyone taking part in our mission.

The next morning the members of my delegation arrived in dribs and drabs. By eleven o’clock we had enough people to begin our first meeting. I told them that we should see it as a great honour that we had been invited to observe the elections in the world’s most extensive country. But I also warned that this would be a formidable task. This would apply as much to the preparatory meetings in the days to come as to election day itself. If you were expecting a holiday, you’d come to the wrong shop. Everyone said that they well understood this.

After this we had the chance to meet and get to know the observers from the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), of which Russia is a member. As a member of both Council of Europe and OSCE, Russia has a duty to hold elections which meet international standards. It was our job to look into this. The OSCE delegation was headed by the president of its parliamentary assembly, Petros Eftimiou from Greece. Later in the day I took the time to have a good talk with him about how we could give concrete form to our cooperation. Speaking with a single voice seemed to us best, which also went for cooperation with OSCE Special Ambassador Heidi Tagliavini, who is in charge of long term observation. I met with her in Moscow at the beginning of November. She is extremely expert, has been active in numerous European countries, speaks fluent Russian and made a good impression with her diplomatic yet candid report for the European Union on the war between Georgia and Russia. As with Eftemiou, I took the opportunity to meet with her on this first day of our mission.

In between all of these appointments I also met with representatives of the parties standing for election on 4th December. They are competing for a total of 450 seats in the State Duma, as the parliament is known, and to win representation must equal or surpass a threshold of 7% of votes cast, although a new rule will allow parties receiving 5- or 6% one seat or two. After these elections the threshold will be lowered to 5%, the level at which the bar is set in Germany. The latest opinion polls predict that four parties will succeed in meeting the threshold: United Russia, the Communist Party, the Liberal Democratic Party and Honest Russia. But Jabloko, the Russian Patriots and Just Cause are also standing, so who knows?

I chaired the meeting along with my Greek OSCE colleague, which was some job. Just like politicians the world over our guests liked to talk, as did the parliamentarians in our own delegations. I tried to get everyone to take a close look, above all, at the electoral process. What’s in their election manifestoes is for us for the moment less relevant, however interesting it may be to read them. I was careful to ensure that each party was given the same amount of speaking time. We were warned to do this, and quite rightly.

After the politicians it was the turn of the media’s representatives. These came in all shapes and sizes, for and against the government, public and private, with contradictory opinions and contradictory information. We had gradually to try to make sense of all this. That was also why we were there. Everyone seemed to agree that for the first time the internet would have a role to play in the elections. What this would lead to was less clear.

The planned meeting with the president of the electoral council was cancelled without explanation. This seemed like a repeat of what happened early in November, when a meeting which had been arranged failed to happen. Just before the end of the official programme I had managed an informal meeting with president Churov. Three days later came his complaint. I was wondering now whether I would have any further contact with him.

The next day, December 2nd, began with an extensive briefing from Ambassador Tagliavini and her team of experts. In just two hours we were brought up to speed with the findings of the long-term observers who had been at work in the whole of Russia throughout November. All of them spoke Russian, which helped them to know what was going on. The experts were also responsible for keeping up with media coverage of the elections. We were presented with a large number of graphics showing how the various TV broadcasters divided time between the different parties. In addition, how things were meant to go on election day was explained in detail, so that our observers would know just what they were expected to do, and not to do. And the recent legislation affecting the elections was explained, all of which was extremely useful.

Tiny Kox at a briefing on the elections with, amongst others, Gary Kasparov

Following this we met with representatives of organisations who were involved in various ways in the political process in Russia. Former chess champion and longstanding opponent of the government Gary Kasparov was there, as was Ludmilla Alexeva of the Helsinki Foundation, who said that things were not going at all well with the election process. From a slightly different perspective Alexei Semenov, from the Centre for Monitoring of Democratic Processes agreed. The fourth person at the meeting was Mikhail Veller, a writer who does not shy away from provocation. To keep everyone short and sweet turned out not to be all that simple, but still things went well. One important absentee was Grigory Melkoniants from the internal election watchdog GOLOS. The previous day the GOLOS offices had been raided by the police and today he had to appear in court. Rumour had it that what was being investigated was whether GOLOS has broken certain rules on election coverage.

In the afternoon we met with Mikhail Kasyanov and Vladimir Ryzhkov. The latter was a Member of Parliament from 1993 to 2007. In 1999 he was asked by Boris Yeltsin to accept the post of vice-premier, but refused. He then founded his own party, but it did not receive permission to stand in the elections in 2007. The European Court of Human Rights has since condemned this ruling, but thus far this has not led to any results. Ryhzkov has now got his own talk show and is a renowned columnist. Kasyanov was prime minister for a while under President Putin, but then fell from grace. Together with Ryhzkov he founded, a while back, a new liberal party. This was, however, once again refused permission to stand in the elections. Both men are extremely critical of all of the parties participating in the elections. Yet both could also be questioned as to how they behaved during the period when they enjoyed a great deal of influence.

On the way back to my hotel I noted how little election activity was evident on the street. Just a lot of United Russia posters, and posters put up by the Central Electoral Council. The similarity between the two is great enough to have attracted international attention, but the Electoral Council has decided that no rules have been broken. The other parties see things rather differently. Official complaints, however, have not been received, the Electoral Council claims, although again others differ. I took note of all of this. I will have a great deal to say in my final report, which will be debated at the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) plenary in Strasbourg in January.

In the evening, because of the presence of my Greek colleague, the Greek ambassador hosted a simple reception. As the Greeks are flat broke, the reception was sponsored. One of the sponsors was – oh dear – Coca Cola.

The next day, Saturday, was the eve of the elections. The day began in the wee hours, with an emergency telephone conversation with the leader of the OSCE delegation, prompted by the increasing pressure being brought to bear on the internal electoral watchdog GOLOS. The organisation had been fined a steep 30.000 roubles for their alleged transgression of the rules. We decided to take note of everything but first of all to see what happened on election day. A few hours later the morning news announced that on her return to Russia GOLOS director Lilia Shibanova had been taken in for questioning by the police. I had met her in Moscow on my previous visit and her information regarding the electoral process had been of great help to us. I was hoping that she would be able to get quickly back to work, as tomorrow GOLOS wants to have thousands of observers in place throughout the country. The actions in relation to GOLOS had led to a world-wide reaction. Everyone is interested in following these elections, not just us.

Later in the morning I had an informal meeting with Konstantin Kosachev, leader of the Russian delegation in PACE and Chair of United Russia’s International Commission in the Duma. We know each other well from PACE meetings, and of course he is curious to know about my findings. Naturally for the time being I’m keeping all of the conclusions that I’ve come to close to my chest. He knows very well that come Monday I won’t be calling for three cheers.

At midday the tasks for the following day were divided between members of the delegation. Those who would be doing their observing in faraway locations had already left the day before, to Vladivostok, to Irkutsk, to Yekaterinburg, and a large group were on their way to St Petersburg. Those staying in the Moscow region were allocated a section of the city in which they would be visiting the polling stations. Moscow is an enormous city, with seven million voters. So we were no more than pinpricks, but a pinprick well wielded can make quite an impression. Everyone was given a driver and an interpreter. We worked as a rule in pairs, for the simple reason that two will see more than one. Everyone would have to be at the first of their polling stations by half past seven in order to be there when it opened, and each team would be expected to visit some ten in total. At the last, the closure and the count would be observed. Between times observers’ reports would be delivered, and on the basis of these all sorts of statistics would be drawn up which we would need on Sunday night and Monday morning in order to judge how election day had gone. I wished everyone good luck and told them to remember that we were there to observe, not to comment, a far from unnecessary reminder given the pressure which we could expect to be under, especially in Moscow. Thousands of youths from United Russia were, I had heard, on their way to the capital for a special congress. They were also keen to make their presence felt in Moscow’s streets and squares, they said, while various opposition movements had also announced demonstrations. Police numbers would be heavy. Elections are still special, even after twenty years or so of experience of them.

At seven o’clock on the morning of election day I was already on my way to the first polling station in the company of a journalist from Vedemosti, one of Russia’s quality papers. They won’t be hearing a verdict from me today, but tomorrow will see the joint press conference with the OSCE where we will list the good and bad points of the election process and its result.

We began in a monumental Stalin era building in the centre of Moscow, once an office block, now apartments of the dearer sort. Far from everyone in Russia is poor. On the contrary. But I didn’t see much of the residents. As soon as the voting booth opened, in streamed a large group of cadets from the nearby military academy. The people staffing the polling booth, most of them women, were doing everything they could to make sure everything went off in good order. It looked somewhat bureaucratic, sometimes lacking transparency, but on a technical level the Russia of 2011 is perfectly capable of organising sound elections.

Further polling stations that I visited in the course of the morning in the centre of Moscow presented the same picture. Well organised, no disorder, and everywhere a friendly welcome for the international observers. At one polling station I bumped into Konstantin Kosachev, who was there with his family to cast his own vote, and who noted that strict rules were in force there, even for him. Because he would be campaigning, he had originally said he would vote at a different locality, but then decided to come along to this one with his family, and it had taken some time and trouble before he received permission to do so.

During the day I talked also to the international observers from the former Soviet republics, the countries which are now members of the Confederation of Independent States. We exchanged experiences, which we all found useful. Cooperation between the Council of Europe and the OSCE does not at the moment form part of this process, which means that differences between standards are too great.

Cooperation with the OSCE observers, on the other hand, went better than many had expected. We were in agreement over our findings up to election day and decided to meet again the following day when the outcome of the elections was known.

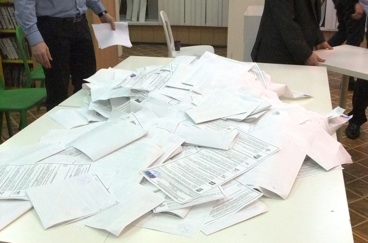

The ballot boxes are emptied

After the meeting I continued observing. At most of the places I called in at, everything was going more or less as intended. That wasn’t the case for the last polling station I went to, the one where I stayed for the closure and the count. Here, everything that could go wrong was going wrong or had gone wrong, including finding strange piles of ballot sheets that came out of the box folded together. That they hadn’t folded themselves was, it seemed to me, clear. But the staff at the polling station had seen nothing. We had, but because we were observers not inspectors all we could do was make a note of it as part of our complete report on how the day went.

Ballot forms prior to being counted

During the night all of the results of our observation were processed via the computer to form a complete, sound record of what we had witnessed of these remarkable elections. Something had happened today in the world’s most extensive country. Voting serves a purpose, and this is also the case in Russia – that much has been made clear. And along with that the Russian people are for the time being the winners.

As it turned out, the day had brought numerous surprising developments. Russian television reported that the big winner of the day was also its big loser. Premier Putin’s and President Medvedev’s United Russia won close to half of the votes but at the same time lost 15% when compared to the last parliamentary elections, an unprecedented event for Russia. Gennadi Zjuganov’s Communist Party almost doubled its vote, rising from 11- to 20%, while the other somewhat left-leaning party, Honest Russia did well, picking up 12%. Zjirinovski’s Liberal Democrats rose slightly to a similar figure, while the liberal Jabloko did best of the newcomers with 3%. So there will be no new parties in the Duma.

Despite this, many Russians would have been rubbing their eyes when they turned on their televisions on the day after the elections. The party that has been all-powerful here for so long and had almost everything in its grip would have to accept a loss of around 15% of its vote. This may have been possible for United Russia, which has until now enjoyed a two-thirds majority in the Duma. But that the party of Premier Putin and President should have dropped below 50% is seen by many Russians as a miracle, which perhaps indeed is what it is.

Journalists gather for the press conference

Personally I found it miraculous that I woke up in time to prepare all of the things which I would have to do during the coming day. Until now I’d been observing the elections, but today I could comment on them. And there was a great deal to be said. To start with I listened to my colleagues from PACE, assembled in the hotel for the debriefing. They all had sleep still in their eyes, which didn’t stop them talking nineteen-to-the-dozen. Our first conclusions: the elections had been well run on a technical level, many people had taken the trouble to vote despite their misgivings, and they had delivered a shock to the authorities with the result. Although election day had gone well, things had gone awry when it came to the count. Some observers were thrown out of their polling stations, others kept well away from where the votes were actually being counted. Still others had to wait hours before the count got under way, the hope obviously being that they would get fed up and leave. And then there was my own experience in central Moscow of finding piles of votes folded together amongst the ‘ordinary’ votes when the ballot boxes were opened, which others had seen elsewhere.

A bit later I recounted our experiences to the OSCE people, who had visited a total of 1,300 polling stations. In 10% of the localities in which they had been able to observe the count they witnessed serious transgressions of the rules, including stuffed ballot boxes like the ones I and others had seen in Moscow. In order for that to be possible the electoral registers must have been falsified, because every voter is obliged to sign when casting his or her vote, so more ballot papers require more signatures in the registers. We added these findings to our own analyses and verdicts as to how the weeks running up to the elections had gone. We didn’t pull any punches. For my part I stressed how the lack of an independent Central Electoral Council had made it impossible to take the result seriously, whatever it may have been. If you want free and fair elections, you can’t manage without an impartial referee.

We went through our findings once again. The long-term observers from the OSCE had all reported. My findings from early November were taken into account, as well as all the reports that we had received last night from our own observers, 350 of them in total. Everyone shared my view that the referee hadn’t come up to scratch, but also that the governing party had been hugely favoured in almost all of the media, especially when it came to television. We also noted that critical websites had closed down, only to reappear in cyberspace immediately the polling stations closed. In recent weeks local and regional authorities had in a considerable number of instances put improper pressure on factory managers and school boards: the lower the vote for United Russia, the lower the subsidies and the amount of available work would be, this was the scandalous message.

The observer teams’ press conference

But we also noted that those who knew long before the election that everything was fixed, nevertheless went solidly along with it. In spite of all the manipulations, the ruling party had to really make an effort. Relations in the new parliament will be rather changed. The majority large enough to amend the constitution has vanished and even the simple majority demanded for any change in the law is not guaranteed in advance. The opposition parties have grown, with the Communist Party on 20% or so of the votes becoming a leading opposition force which cannot be ignored. CP leader Gennadi Zjuganov, who last Thursday distinguished himself in the number of complaints he lodged regarding manipulation by the authorities, is now continually depicted as a winner. I’m looking forward to January, when together with his right-hand man, Ivan Melnikov, he will put in an appearance at the PACE plenary. Both are members, and both are, remember, members of the same United Left Group of which I am Chair. You can bet they’ll be proud of themselves. But that day they looked on the television more than anything tired, dog tired. They must have also been through a lot in the last few months. They’ve collected piles of complaints. We must wait and see whether the three parties which along with United Russia will form the new Duma also develop into serious opponents of the Putin party.

A great deal of effort had been put into the production of an extended report of our combined international observers’ mission, as well as a common declaration, after which there remained a joint press release to be done. From two o’clock the world would move on. But first the press conference. The room in the Marriott Grand Hotel was packed. Lots of people from the press, lots of cameras and microphones. First up was Petros Eftimiou of the OSCE who gave our general findings. Then I spoke, emphasising that votes really count in Russia thanks to those who had turned out yesterday, and that there was more than ever a need for an impartial referee and a level playing field.

Ambassador Tagliavini from the OSCE then informed those present about the statistical findings of our 350 observers. For a whole hour we took the most varied list of questions and after that gave the necessary one-to-one interviews. Until people began to attract my attention to let me know it was time to leave for the airport. On the way in the car I texted various colleagues to thank them and give my apologies for my sudden departure. But aeroplanes don’t wait. At the airport I had the chance to speak to various Dutch media people. Russian newspaper Izvestia also called, who wanted to know, amongst other things, what I was going to do next. Senate meeting tomorrow, I told them, and then work hard to prepare an extended report that will be presented in Strasbourg in January. But first a glass of beer. What it cost I don’t know, but it was at least a Leffe blonde. As I have noticed throughout my visits, in many ways Russia is becoming ever more European. As we say in the Netherlands when we raise a glass, ‘Proost!’.