Financial-economic crisis: economic stagnation postponed

Financial-economic crisis: economic stagnation postponed

The financial-economic crisis is often blamed on irresponsible behaviour on the part of banks and on inadequate supervision. These do indeed play a role, but the causes of the crisis lie deeper. Significant change in macro-economic income distribution in the US and the EU countries since 1980 brought about the development of potential economic stagnation, the realisation of which was advanced in time by the way in which the banks were operating. Now that the crisis gives the appearance of coming to an end, stagnation is seizing its opportunity.

Geert Reuten is Professor of Economics at the University of Amsterdam and a Member of the Senate for the SP

Wage restraint without an increase in investment

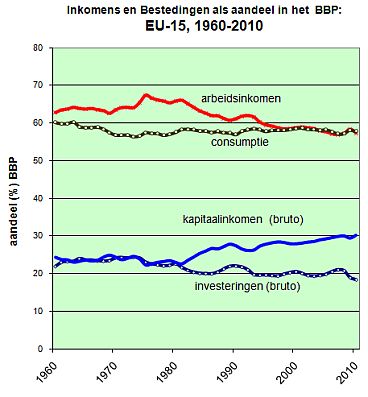

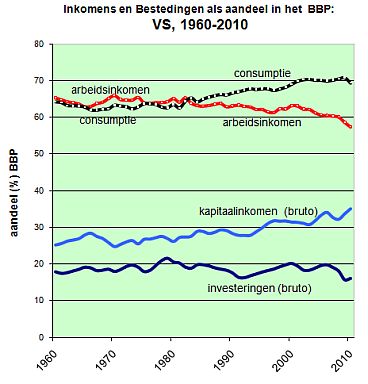

With the recession of the early 1980s mass unemployment arrived in the US and the member states of the EU. This brought a shift in power relations between employers and workers, through which wage increases lagged persistently behind increases in labour productivity. We can see this reflected in the fall in the share of the Gross National Product (GNP) going to labour. This labour income share has fallen in the US and the EU countries by 12-15% during the last thirty years, during which time the share going to capital incomes has risen by 35%. This did not, however, result in a relative rise in investments. On the contrary, the share going to gross investment fell by 12-16% . This is remarkable because the 'need' for wage restraint has always been advocated on the basis of the need to increase investment. Workers moderated their wage demands while employers failed to increase investments accordingly. The graphics below demonstrate this development, showing that in the EU countries a large 'gap' appeared between capital incomes and investments, while in the US an already existing gap grew wider.

Incomes and investments as a share (%) of GDP, EU-15, 1960-2010

Incomes and investments as a share (%) of GDP, US, 1960-2010

The red line shows labour incomes, the line alongside it consumption, the light blue line capital incomes and the broken blue line (top graphic)/dark blue line (lower graphic) investments.

Relative fall in wages and rising consumption

Under 'normal' circumstances a relative fall in wages will result in a relative fall in consumption. In the face of the persistent strong fall in the share of income going to labour that we have seen in the US and to an even greater extent in the EU, a corresponding decline in the share going on consumption would lead to stagnation: a fall in wages leads to a fall in consumption, and thereby to a decrease in production and investment and thus to redundancies, the result of which is a further decline in production, and so on. However, the circumstances were not 'normal'. As the graphics show, in the EU countries see a continual fall in the relative wage share from 1975-81 onwards, yet consumption remains almost stable! This can to only a relatively limited extent be explained by increased consumption of profit income. The explanation lies in the combination of declining savings with a rise in consumer credit. In the US one can even see, in the face of a relative fall in wages, an enormous rise in consumption! But in the EU too we have seen, in the last ten years, a share devoted to consumer spending which is slightly higher than the share going to labour.

Colonisation of the future

Relative wages decline, savings dry up, and the banks were so good as to leap in with consumer credit, directly in the form of consumer loans, indirectly via mortgage extensions on the surplus value of houses and apartments. Workers could by these means maintain and even increase levels of consumption. In this way they also prevented economic stagnation.

But loans carry interest, and in the end must be paid back. Banks, and through them other providers of credit, in this fashion lay a claim to future wages. Thus what we see is a 'colonisation of the future'. Wages, falling in relative terms from 1980 onwards, are 'compensated for' by credit. But this means that disposable incomes will be lower in the future. So stagnation is in this way delayed.

Coincidence of interests

Through a coincidence of diverse interests everything seemed, until quite recently, to work out.

- The super-rich were seeking investment opportunities. Banks sold extensive loans to workers in order to fund high-powered investments ('securitization'), effectively becoming 'colonizers of the future'. Between 2000 and 2007 this form of selling by American and European banks quadrupled from $400 billion to almost $1600 billion dollars.

- The banks themselves earned interest on the consumer credit which they themselves managed and, via commissions, from the resale of loans. Resale then created space for further consumer lending.

- Firms must as a rule 'pre-finance' their sales via bank loans in order to meet their monthly salary payments. Yet with consumer loans to workers, these workers can make purchases from companies thus to this extent the 'prefinancing' is no longer needed. This means that the companies in question pay less in interest to the banks. (The banks compensate for this with higher interest on the consumer loans.)

The super-rich remain the least damaged by the crisis: banks give all sorts of guarantees in respect of the resold loans. The banks are in trouble, but their losses are passed on: they must not be allowed to go bankrupt, so the taxpayer has to step in. Corporations received a severe setback, but they are not in the forefront when it comes to making the case for radical change in the banking system. And of course, the biggest burden of misery is shifted to the shoulders of the unemployed.

Stagnation problem has not been solved

The financial-economic crisis is the expression of the reaction to the changes in income distribution since 1980. The potential stagnation problem itself has not been solved by the crisis. On the contrary:

- If the banks are to be dealt with effectively, so that a collapse of the whole system no longer threatens, then it will be done by means of pushing the problem further back. Consumption's share will fall.

- In addition, a colonisation claim is being laid to future workers' incomes, which will also bring about a relative fall in consumption.

- Firms, as a result of this relatively falling consumption, invest less.

- Tightening of state spending affects public provision but also leads to a fall in companies' sales.

- Countries such as China and India will not allow the US and EU to increase their exports without a corresponding increase in imports. So this offers no solution.

All in all the economies of the US and the EU are going to find themselves in a period of stagnation.

What is to be done?

Firstly, a deep recession is the worst moment to lower public spending. A temporary 'crisis tax' of 2% on the richest would offer sufficient reduction in the budget deficit. Hard to swallow for the rich, but stabilisation is in their interest too. This would address the short term problem.

Secondly, stagnation leans to a drying up of profits and returns. In order to avert this, wages must, more or less gradually, be subject to strong increases. Of course, an individual firm wants to pay out the lowest wages possible, but an individual firm does not control its own market. To avoid worse, companies must adjust to lower returns than they have enjoyed in recent decades. Such returns are mere habits. Strong increases in wages would be in the interest of the workers but also in the interest of firms.

The big question is how this collective reasoning can come to prevail in an individualistic market economy. Unions changing tack? Employers' organisations operating in an unorthodox fashion? Should such actions not appear spontaneously, then the authorities in the US and the EU member states must bring about a corresponding effect through changes in the system of taxation. But that would require a change in political relations.

This article first appeared in Dutch in the national daily financial newspaper Financieele Dagblad of 21st August 2010.