Bolivian referendum: Impressions of the SP's official observer

Bolivian referendum: Impressions of the SP's official observer

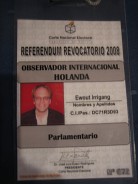

Earlier in the month SP Member of Parliament Ewout Irrgang, spokesman on development issues, and parliamentary advisor Riekje Camara spent ten days in Bolivia, observing the referendum of 10th August on whether President Evo Morales and a number of regional opposition governors should remain in office.

Only in 2005 did Bolivia at last elect a president of indigenous origin. Under the presidency of Evo Morales, Bolivia has come to play a leading role in the struggle against neoliberalism in Latin America and the wider world. Irrgang and Camara were in Bolivia to exchange ideas with the progressive government and also to meet representatives of the opposition.

Irrgang has participated in the campaign to oppose the payment of compensation to foreign investors who claim to have lost money when the water company in Cochabamba, Bolivia's second city, was taken back into public ownership, and against the telecom corporation ETI. The latter, an Italian transnational, used a box number in the Netherlands in order to take advantage of a Netherlands -Bolivia investment agreement. As well as taking part in demonstrations on these issues, Irrgang has put parliamentary questions on a number of occasions in an attempt to put pressure on the Dutch government.

Ewout Irrgang kept a diary of his experiences in Bolivia, a summary of which, and some highlights, are below.

3rd August

Arrive in the capital city, La Paz, after a long night-flight. The airport is 4000 metres above sea level, high even for La Paz. Here, higher means poorer, and the airport is surrounded by El Alto (´the high one'), a suburb inhabited by poor Indians.

We'd been warned about altitude sickness, so had managed to book a hotel at a mere 3200 metres. We slept well and the next day took it easy. No appointments, though apart from a slight headache we both felt fine. So in the afternoon we hired a taxi to take us around the centre and up to Lake Titicaca on the high plains above the city.

Everywhere we went we saw slogans: 'Evo si' - 'Evo si se queda, Bolivia te pide' (‘Evo we want you, Bolivia is asking for you') and ´Salud antes para pocos, Ahora para todos' ('Health in the past for the few, now for everyone'). Politics is big here. You see more political advertising than commercial, and Morales is clearly very popular. Not surprising, because La Paz and the high plains are part of his power base. The opposition is concentrated more in the richer regions outside the capital, home of the gas industry recently nationalised by Morales.

4th August

Became ill in the night with what the doctor said was a combination of altitude sickness and food poisoning. Riekje was okay, but hadn't got much sleep. Still, the programme had to begin all the same. La Paz was ready to party, this being two days before Independence Day, and the streets were already blocked by parades of students.

At the Ministry of Foreign Affairs we met with the Director General for Bilateral relations, Jean-Paul Gueverra, who told us that in Bolivia what was happening was a democratic revolution on three levels.

Firstly, it was socio-economic, as Bolivia is the poorest country in South America and something had to happen about the enormous inequalities in the country, for example through land reform.

Secondly, it was a cultural revolution. Most people were Indians, but the white tribes of Spanish colonisers had always pulled the strings. So, for example, bilingual education was being introduced in order to further the emancipation of the indigenous peoples.

Thirdly, this was an institutional revolution. The state must become less centralised, with a new constitution which would be put to the people at the end of the year. The opposition wanted to see decentralisation go much further.

We met later with the Dutch ambassador and the embassy's development specialist, who took a positive view of Morales, even comparing him to Nelson Mandela as another first indigenous president. Later we were supposed to meet with oppositionists, but the meeting was cancelled. The opposition Prefect of Santa Cruz, the capital city of the opposition, was said to be on hunger strike, though in Bolivia this usually means that as soon as the journalists' backs are turned you tuck in. We decided to drop in anyway. Surely a man on hunger strike would want to explain why?

5th August

Santa Cruz is everything La Paz isn't. Green, tropical, and opposed to the Morales government. As for me, I feel a bit better, probably because down here in this low-lying part of the country I can breathe again.

In the morning we visit FAN, the Friends of Nature Foundation, which receives aid from the Netherlands. Because the country has so many different climate zones, Bolivia has enormous biodiversity. Twenty percent is national park, and if you add regional protected areas to that it comes to more than half of the country. Deforestation is a major problem. FAN's approach is to try to encourage sustainable management rather than a hands-off approach. We were told, for example, how FAN has supported the gathering of wild cocoa by local Indians, and its use to make chocolate. This gives the Indians an income, combating poverty, and also an interest in conserving the forest.

After lunching with the vice-president of CIDOB, which represents the Indians of Bolivia's low-lying tropical areas, a supporter of the government. Then we pay a surprise visit to the opposition. What we see when we arrive are mostly burly men and slim girls, all wearing the lily-white teeshirts of the local employers' group, demonstrating just what interests lie behind the autonomy movement.

We get to speak to Blanko Marinkowic, president of the Civico Committee and said to be the power behind the throne of the Santa Cruz prefect. A cowboy fluent in American, he has no time for Morales. There is no marginalisation of Indians or racism against them, he says. The elections were rigged. The Organisation of American States (OAS) had confirmed that multiple voting cards were issued to Indians. And so on. Our local guide told us afterwards that at least half of what the man said was untrue, while a member of our own embassy's staff said that the OAS had in fact found only 2% of votes were false, a low rate for a big country like Bolivia. Still, I agree that MAS, the Movimiento al Socialismo, has made a mistake in not going further with the decentralisation programme in a country which is historically over-centralised. The proposed decentralisation is favourable to the Indians, but somewhat more autonomy for the regions would not be unreasonable. Certainly not, however, in the way desired by Santa Cruz, under whose proposals tax incomes would almost all remain in the region. The fact that gas profits come from the rebellious regions is of course no coincidence.

The kind of lying politics we encountered in the person of Marinkowic has long held the white settler elite in power in South America – not forgetting violent support from the US. The time of military dictatorships seems now, for South America, truly past. Numerous left governments are trying to tackle enormous inequalities, and the elite, including in Bolivia, is still having trouble accepting that.

6th August

Independence Day in Bolivia. In Santa Cruz the party and the colourful parades are divided, the Indians sporting the colours of Bolivia, the whites the green and white of Santa Cruz.

We visit the parades in the main square, where we hear opposition leader Costas describe the Morales government, led by a man who won 54% of the votes, as "totalitarian".

7th August

First meeting is with Rocio Mullor of Bolivia Transparante, a recently established organisation that works hard and effectively to ensure fair elections. In the afternoon we have an official visit to the Ministry of Hydrocarbons and Energy, where we hear how the Morales government reversed the privatisation of 1996 which, not having been approved by parliament, had in any case been illegal. This privatisation meant that 82% of the profits had gone to the corporations involved, and only 18% to the state. Now these figures have been almost reversed, and the state receives 80%. At the same time, the contract with Argentina for the supply of gas has been revised so that Bolivia receives far more income. Total income has thus risen in two years by $200mn. to a total of $1.9bn. Refineries and transport firms have also been nationalised, successes of the Morales government of which even the opposition had made no criticism.

First meeting is with Rocio Mullor of Bolivia Transparante, a recently established organisation that works hard and effectively to ensure fair elections. In the afternoon we have an official visit to the Ministry of Hydrocarbons and Energy, where we hear how the Morales government reversed the privatisation of 1996 which, not having been approved by parliament, had in any case been illegal. This privatisation meant that 82% of the profits had gone to the corporations involved, and only 18% to the state. Now these figures have been almost reversed, and the state receives 80%. At the same time, the contract with Argentina for the supply of gas has been revised so that Bolivia receives far more income. Total income has thus risen in two years by $200mn. to a total of $1.9bn. Refineries and transport firms have also been nationalised, successes of the Morales government of which even the opposition had made no criticism.

We could learn a lot from this in the Netherlands, where 50% of the profits from gas still go to Shell and Esso. The SP's proposal for an additional levy on profits is comparable to what Morales has done in Bolivia, though relatively meagre. Why shouldn't we take 80%?

After this inspiring meeting we met with Guido Rivero Franck of the Bolivian Foundation for Multiparty Democracy and opposition MP Carlos Birdt. The latter argued that the desire for more autonomy for the regions was comparable to the autonomy offered to the Indians in the proposed constitution. He also said that land ownership was a crucial point of contention. The region wanted to control any reform, but the proposed constitution would give control to the central government.

No coincidence that in Santa Cruz twenty-seven families own almost all of the land. Clearly they fear land reform and are trying via autonomy to protect their interests.

After that we had a pleasant evening with To Tjoelker, number 2 in the Dutch embassy, and her husband. He cooked us a splendid meal, being both a chef and a member of the SP.

8th August

It's snowing in La Paz. The Bolivians tell us that this is a sign that winter is almost over, but we're freezing cold as we enter the Ministry for the Judicial Defence of Recovered Subdivisions of the State, a new body which seeks to protect Bolivia from western firms such as Shell and ETI, which are demanding compensation at the World Bank. The Minister, Hector Arce, explains how the negotiations with foreign enterprises are going. With Shell the answer is reasonably well, but in the case of ETI this is decidedly not the case. He expresses regret that the corporation is not open to dialogue and has instead chosen to begin legal proceedings. Bolivia does not want to give the impression that it is hostile to foreign forms or investments. He welcomes all investment in his country, he says, but the price of this must be just and it must benefit the Bolivian people, especially the poor. .

9th August

Bolivia is preparing for tomorrow's referendum. We receive a note from our hotel telling us that the government has decreed that no alcohol can be sold during the 48 hours leading up to it. Tomorrow only cars with special permits will be allowed on the roads. The Bolivians find all of this extremely exciting and so do we. All opinion polls point to a Morales victory, but polls are often wrong, so we won't really know until tomorrow evening.

Having already had our official observers' cards from our own embassy, we receive a lengthy letter from the National Electoral Court. The Bolivians will have to answer two questions. "Should the president and vice-president remain in office?" and "Should the regional prefects remain in office?" Now, if we had the chance to send the government packing in the Netherlands through a referendum, the opposition, or certainly the SP, would be overjoyed. In Bolivia, however, it's the government that wanted the referendum, while the opposition was against. This reflects the expectation that Morales would win and also that a number of opposition prefects would be cleared out, though certainly not in Santa Cruz. The somewhat remarkable referendum law says that more than 54% of the people must vote against Morales before he has to stand down, this being the percentage that voted for him at the election. But if a prefect doesn't score 50%, Morales gets to replace him.

Today we are given an explanation of how the polling booths should be opened, how the votes will be counted, and the four ways in which voters may identify themselves.  We have complete freedom of movement as to where we do our observing. Everything seems reasonably professional, but this is a country which has already had two decades' experience of democracy. Fraud is difficult here. All we have to worry about are disturbances hampering voting. There are about a hundred international observers, and we chat with a member of the Chilean high court who is here as one of them. After the briefing we talk to a member of the National Electoral Court. He's quite happy to have so many left parliamentarians from other countries as observers. His own views become clear when he advises us not to go to Santa Cruz, where "pre-civil war" conditions would prevail. Yet Bolivia has had many years of democracy, the army has said that it will not intervene, and despite all the strikes, blockades and occupations which the country has seen, strikingly little physical violence has occurred.

We have complete freedom of movement as to where we do our observing. Everything seems reasonably professional, but this is a country which has already had two decades' experience of democracy. Fraud is difficult here. All we have to worry about are disturbances hampering voting. There are about a hundred international observers, and we chat with a member of the Chilean high court who is here as one of them. After the briefing we talk to a member of the National Electoral Court. He's quite happy to have so many left parliamentarians from other countries as observers. His own views become clear when he advises us not to go to Santa Cruz, where "pre-civil war" conditions would prevail. Yet Bolivia has had many years of democracy, the army has said that it will not intervene, and despite all the strikes, blockades and occupations which the country has seen, strikingly little physical violence has occurred.

10th August

At seven o'clock the next morning we present ourselves at the National Electoral Court. After the inauguration ceremony attended by the international press, and held in the garden – despite a temperature of 3 degrees! - we go in search of the President of the Court to make sure that it's okay for us to leave La Paz. He issues a special plate for our car, and obviously sees it as important for the credibility of the international observers that we don't all remain in the capital.

After visiting a number of polling boots in La Paz, we go to Coroico, about two hours away along a beautiful road through the Andes, about 5000 metres up and under snow. On the way I stop for a telephone interview with the Dutch World Service. I tell them that all is going well, that the only trouble we have seen was at a polling booth which could not be opened on time because not all of the necessary personnel had arrived.

We arrive at Coroico around noon. There are long queues at the polling booths. Although they're clearly less used to international – blonde – observers here, we are given a warm welcome. There seems little possibility of fraud or intimidation.

Back in La Paz after a journey back through the mountains, the streets are even busier than they had been in the morning. A spokeswoman for Bolivia Transparente tells us that only in Yacumo in Beni province have there been reports of any problems. The overall picture is good, and this fits with our own observations, though later we hear that there have also been incidents in Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, and even in La Paz. But the spokeswoman assures us that these were isolated reports and that the general picture remains good.

Lastly we visit El Alto. The atmosphere here as elsewhere is pleasant, and the votes have already been counted, with Morales receiving 90%. Back in La Paz, we hear that the exit polls are giving him 60%, well up on the 53.7% he received in the last election. The prefects of Cochabamba and La Paz have been voted out, but those of Santa Cruz, Beni and Tarija have won by handsome percentages and can remain in office.

So the opposition can also claim a victory, and it might be an intelligent move for Morales to make some sort of gesture towards the people of these regions from his new position of strength. But that is for the future. Today's referendum seems to have gone off peacefully. The Bolivians have made it into a party, and I feel proud for them.

11th August

The official result won't be out until the beginning of next week, but the paper in our hotel gives Morales 63.5% and others give him a few points more or less. Clearly Bolivia wants the 'cambio' – the change – to continue. Even in Santa Cruz Morales scored over a third of the votes and in opposition Beni 50%. And the President is making conciliatory noises towards these regions in relation to the new constitution. We talk with a MAS Senator whose brother fought alongside Che Guevara, and he also argues in favour of dialogue with the opposition.

At the end of the afternoon we give a report to the embassy, adding two things which I haven't mentioned so far in these notes. Firstly, development cooperation: we agree with Morales that his country does not need aid. He wants to see an end to it within ten years. The SP's view is that development aid should be directed towards the very poorest countries. Bolivia is South America's poorest country, but certainly does not belong to the poorest countries in the world. This country has primarily a problem of division, not so much a problem of development.

The Netherlands should certainly ensure that trade- and investment treaties do not hinder Bolivia's development. International negotiations over a free trade and association agreement present a threat to poor farmers and to Bolivia's chances of building up its own industries. The bilateral investment treaty with Bolivia is leading to a situation in which devious multinationals such as ETI are attempting, via box number companies in the Netherlands, to trick the Bolivian government out of its money.

We also discuss the subject of coca. We are pretty enthusiastic about our mate di coca, and it astonishes us that we can't take this simple herb tea back to the Netherlands. We completely agree with Morales that a distinction should be drawn between coca and cocaine. You might as well ban the French from growing grapes. It is particularly unfortunate because rigid international agreements are depriving Bolivia of export opportunities. Legalisation of coca would provide a good alternative for the coca crop, which is indeed used to make cocaine. The Netherlands should be arguing within the UN for a relaxation of these rules.

We also discuss the subject of coca. We are pretty enthusiastic about our mate di coca, and it astonishes us that we can't take this simple herb tea back to the Netherlands. We completely agree with Morales that a distinction should be drawn between coca and cocaine. You might as well ban the French from growing grapes. It is particularly unfortunate because rigid international agreements are depriving Bolivia of export opportunities. Legalisation of coca would provide a good alternative for the coca crop, which is indeed used to make cocaine. The Netherlands should be arguing within the UN for a relaxation of these rules.

Tomorrow we leave Bolivia. It is impossible to do so without a feeling of sympathy towards the Morales government, for the overwhelming support of the people for the process of change which is sweeping away the residue of twenty years of neoliberalism. Happily, after our time in the country we are optimistic that this process, the cambio, will eventually succeed. Back in the Netherlands we are working towards the same ideals.